In the early 1990s, I began visiting Banaskantha in Gujarat on a regular basis, working with local women artisans to create garments and soft furnishings for the Self-Employed Women’s Organisation (SEWA).

Most were pastoralists, living in villages within a 100-kilometer radius, with husbands who worked primarily in agriculture or as cattle herders.

The area was a desolate, salty wasteland that was prone to periodic droughts and was extremely poor.

The nearest town was Radhanpur. The small dark homes of the Mochi community were in one section, linked by winding lanes.

Traditional shoemakers once employed by royalty, they were now perilously poor, as fewer and fewer people ordered their beautifully embroidered leather juthis, preferring branded, industrially-manufactured shoes, or even plastic sandals.

The advent of the motor car also marked the demise of their elaborately embroidered leather trappings for elephants, horses and camels.

In order to eke out a living, the Mochis turned their hands to making generic embroidered ornamental wall hangings and cushions in fabric rather than leather for local traders and GURJARI, the Gujarat State Handicrafts Corporation. Few other employment opportunities existed.

The men cut and stitched the items, and the women filled in the embroidery, using the traditional aari, which looks like a crochet hook or a cobbler’s awl mounted on a wooden handle, as opposed to the chainstitch embroidery done in Northern India, which uses a straight needle and works on a large, floor-mounted frame.

Similar Mochi communities existed in Bhuj and Mandvi in Kutch, as well as Saurashtra and Sind. In fact, many Mochi families traced their pedigree and craft from ancestors in Sindh who were brought to the Kutch court by Kutchi rulers in the 14th century and encouraged to teach their craft locally. Bhuj, as the seat of the Kutchi royal family, was the largest centre of Mochi embroiderers, now sadly diminished to a handful of families. A few beautiful old carved wooden houses, relics of better days, and some fine tombs, temples and mosques relieved the dusty poverty and small town clutter.

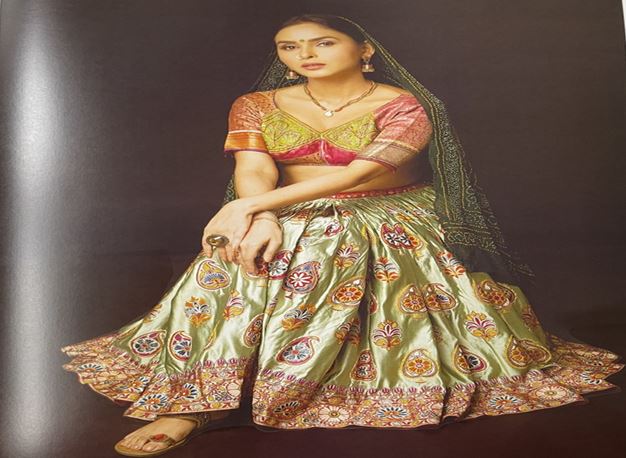

Working on fabric was nothing new to the Mochi community. In the past too, the most skilled craftspeople custom made beautiful garments, accessories, canopies, and wall panels in silk, satin and mashru for the local nobility, and even for more far-flung royal patrons.

The workmanship was extraordinary, the aari used like a miniaturist’s paint brush; the embroidery, delicate configurations of foliage, flora and fauna – peacocks and parrots for fertility; elephants, lions and horses for power and wealth; decorative borders overflowing with the roses and lilies and flowering trees seldom seen in those dry climes.

Verdant Trees of Life were a popular theme, as were Sri Nathji pichwais to hang behind the deity in the temples. Extraordinarily fine work was being done both on leather and fabric well into the 20th century, declining post-Independence, coinciding with the decline of the Nawabs and Maharajas who were their patrons.

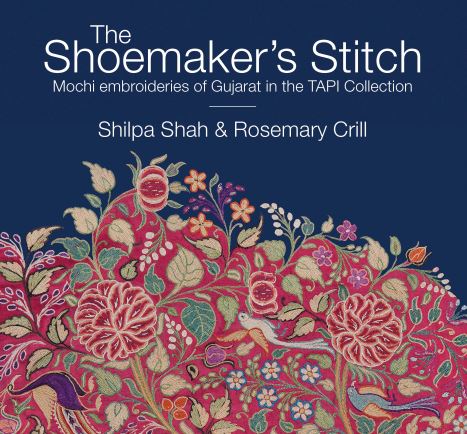

It is these Mochi embroideries, mainly of the early 19th century, that are the subject of The Shoemaker’s Stitch, the latest documentation of TAPI’s wonderful textile collection.

Shilpa Shah, co-founder of the TAPI Collection of Indian Textiles and Art, is also co-author of this book. Her inspirational work, collecting and documenting Indian textiles, follows on from Gira Sarabhai and the Calico Museum in the 1950s and 60s. Her travels all over India and Master’s degree from Berkeley University endow her with both academic and personal insights, as well as passion and love.

Her co-author is Rosemary Crill, former Senior Curator at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, who has studied and written on Indian embroideries and textiles over the years. Their combined expertise and scholarship make this book an intensely pleasurable read – both visually and in its content. On its part, Niyogi Books has done a wonderful job of photography, printing and design. The Shoemaker’s Stitch is a a joy in everything except its considerable weight!

The book documents items from the Kutch, Dhangadhra and Jaipur royal family collections, the V&A and other Western museums as well as pieces from the TAPI Collection itself. It is superbly illustrated: the rich, vivid reds, greens and yellows and ornate, heavily-worked motifs of the Mochi embroideries, often boldly outlined in black, highlighting their difference from the more subtle, delicate Persian and Mughal influenced chainstitch of Northern India and Bengal.

Even pieces commissioned for the European Market have a distinctive difference from the crewel work of Kashmir or the painted chintzes of the Coromandel coast. As Shah points out, Mochi embroideries travelled to courts and temples all over India, and therefore, have often been mistakenly identified as local work. To the trained eye, they are very different, both in imagery and execution.

Looking at earlier craft and textile traditions, it is easy to fall into despair about their present status. However, all is not gloom, as the concluding chapter of The Shoemaker’s Stitch tells us.

Aari bharat has experienced a revival, with many designers and practitioners creating wonderful contemporary pieces, though not always by traditional Mochi embroiderers. Some names that come to mind are Asif Shaikh, Arun Virgamya, Adam Sangar and their extended families, the Shrujjan Museum, and Shobhit Mody.