Ahmedabad: On the morning of 9 November 1874, an Englishman called Robert Phayre unexpectedly felt an assault of sickness in regal Baroda. The moderately aged Colonel Phayre was a British Resident at the Maratha court here and had been to some degree sickly for a very long time earlier. Toward the beginning of that day, however, it was unique. He had, of course, gotten back from his walk and taken a couple tastes of the pummelo sherbet his workers consistently kept prepared.

Sitting down to write a letter, however, a ‘sudden squeamishness’ possessed him. Deciding it was the juice, he threw out the rest, only to notice something odd. ‘As I was replacing the tumbler on the wash-hand stand,’ Phayre recalled, ‘I saw a dark sediment collected at the bottom.’ Holding it closer to the eye, ‘the thought occurred at once to my mind that it was poison’. He sent off the substance for analysis, and telegrammed his superiors: ‘Bold attempt to poison me this day has been providentially frustrated.’

Interestingly, despite the gravity of the claim, when the local maharajah came to see him hours later, the Resident kept mum; it was days before the incident was broached, news having reached the palace through other channels. In his official commiseration, the ruler expressed horror at this plot by ‘some bad man’ to liquidate the Resident. ‘If it becomes necessary for you to obtain my assistance in proving the criminal’s guilt,’ the maharajah offered, ‘the same will be given.’

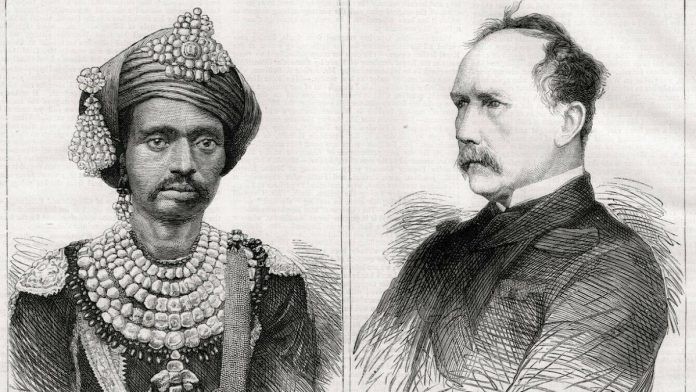

Unfortunately for Malhar Rao Gaekwad of Baroda (1831–82), in Phayre’s mind the ‘criminal’ was none other than the maharajah himself. Ever since his arrival in the principality, the colonel had found himself unable to get along with its ruler. Neither was, to be fair, a particularly placatory type.

Baroda was a case study in what the British deemed misgovernment. Its Maratha rulers were originally conquerors in Mughal Gujarat, subject to the Peshwas of Poona. By the nineteenth century, however, they obtained independence from the Peshwas with aid from the East India Company. Territories were carved up between the British and the Gaekwads in a way that the kingdom came to comprise several disconnected tracts. Then, in 1857, during the Great Rebellion, Khande Rao (elder brother to Malhar Rao) stayed loyal to the Company, for which the dynasty was granted second highest rank among India’s princes. This was why, despite a deepening crisis, colonial authorities did not intervene excessively in the state’s affairs. The Maratha elite were disconnected from their Gujarati subjects, and Malhar Rao did little to improve things when he succeeded his brother. On the contrary, he seemed capable of surpassing him in immoderation. Residents ventured the occasional menacing ‘advice’ but wrote much of this off as typical oriental conduct – that is, till Phayre decided to tutor Malhar Rao in good governance as well as princely morality.

However lofty their intentions, the British could not arrogate a vassal’s authority without giving him a chance. So, in July 1874 the maharajah was placed on probation: he had under eighteen months to address grievances about his government.

As it happened, Malhar Rao too had gauged that reform was a form of defence. So much so that months before the viceroy’s communique arrived, the maharajah had already selected a new Dewan – a figure Phayre described as his ‘principal adviser’ from as far back as 1872. The Resident did not approve, because the appointment was made without consulting him; eight months later, in fact, the colonel was still urging his superiors to refuse to recognize the Dewan, not only because he was ‘incapable’, but also because his ‘line of conduct’ left much to be desired.

But Phayre was not chastened. After all, the new Dewan was none other than Dadabhai Naoroji, one day to be celebrated as the Grand Old Man of India, and declared by Gandhi himself as the father of the nation and a veritable mahatma.

—

The suave, erudite and anglicized Naoroji (1825–1917) was an unusual choice for Dewan in a state where, so far, the cabinet had featured the maharajah’s brothers-in-law and a host of royal toadies. Baroda seemed to be in a state of decay, unlike cosmopolitan Bombay where Naoroji was reared. And yet the man embraced the opportunity, sailing all the way from London, where he was living. As his biographer Dinyar Patel explains, to Naoroji, who lamented the drain of wealth from India to Britain, a key strategy in response was to advocate for Indians, rather than Europeans, to take charge of public administration. Any serious hope of self-government in the subcontinent would depend, he felt moreover, on experiments in the princely states, where native rule could distinguish itself. ‘What a splendid prospect is in store for the future’, he exclaimed, if only the British allowed princes to govern without interference.

Understandably, Phayre was not thrilled with the new minister’s nationalist propensities.

It did not take long for the minister to learn that he was handicapped in multiple ways. On the one hand was the bitter obstructionism of the Resident, who took an age to acknowledge even Naoroji’s existence. Then, on the other, was the fact that while some officials from the earlier system were dismissed, many were not; indeed, the last minister was retained in a palace post, resulting in a kitchen cabinet at odds with the Dewan. Unlike Ayilyam Tirunal in Travancore who embraced reform, Malhar Rao wished only for its appearance. Soon relations between ruler, Resident and Dewan were comprehensively fractured.

It was in this disturbed context, then, that Phayre discovered diamond dust and arsenic in his sherbet that November morning in 1874.

And from his perspective, there was reason to suspect the ruler. On the one hand was the maharajah’s continued umbrage at the delay in recognizing his son as heir to the throne. Then there was political animosity. A week before the poisoning, on the same day that the maharajah fired off a volley of complaints against the Resident to the viceroy, the latter too submitted a 174-point ‘progress report’ that showed Baroda as doomed. It was intended to damage the Dewan as well as the still-on-probation ruler. Frustrated, Naoroji realized he had had enough, deciding to resign. British officials in Calcutta were, naturally, in a bind. Having themselves reprimanded Phayre, they could hardly evade the maharajah’s charge that the Resident ‘prejudged’ everything and had produced a biased report. Equally, though, Malhar Rao was not the kind of ruler who inspired sympathy. The only course available, in the viceroy’s mind, then, was to sack Phayre and send in a mature man.

Phayre, true to form, did not take these developments in the right spirit. At first, he tried to dig his heels in, and when he left, made an almighty fuss. His successor in Baroda, meanwhile – Lewis Pelly, who, interestingly, would win a Commons seat in the same election where Naoroji first stood as candidate – decided to investigate the poisoning. This was chiefly because though ‘[n]o evidence of any value was procured’, Phayre kept insisting the matter be looked into. His perseverance paid off: Pelly found that the ruler had ‘secret communications’ with Residency servants, two of whom confessed to the poisoning. After seeking legal opinion in Bombay and Calcutta, then, the viceroy decided there was a prima facie case against Malhar Rao. From here on, things moved fast. By January 1875, troops were landed, the maharajah was placed under house arrest, and the government – just as Naoroji departed – was assumed by the Raj. Though Malhar Rao, by the viceroy’s own acknowledgement, had not had a chance to put up a defence, examine witnesses or explain his version, the British opted to pre-emptively seize power till he was cleared. ‘This action,’ the viceroy explained, ‘was not based on considerations of law. It was an act of State, carried out by the Paramount Power.’ Elements in the press too had paved the way for this. As an editor put it, ‘The only way to clear the Vessel of Baroda is, to throw over-board its cargo of Rogues.’

But trying a maharajah was no easy business: he could not be dragged before a British court, nor was a public inquiry fitted to his dignity. Still, in the end, an inquiry was less embarrassing. Notwithstanding Malhar Rao’s reputation, this too, in native circles, caused protests – insulting one of the country’s princes was seen as an assault on Indians as a people. Did this dangerous precedent mean, additionally, that other thrones too were not secure?

Under pressure, therefore, the British were forced into a ‘gesture of equality’: of six commissioners chosen for the inquiry, three were Indians: the Maratha king of Gwalior, the Jaipur maharajah and Sir Dinkar Rao, north India’s leading statesman. In the meantime, Malhar Rao too, hoping to fight fire with fire, imported the British barrister William Ballantine to argue his case. The choice was strategic, for, as Judith Rowbotham tells, while this genius was a spectacular misogynist, the one thing he was not, by contemporary standards, was a racist. Ballantine, who till then had had no idea even of Baroda’s existence, decided to do what he did best – try and win. For he too was aware that this was more than just a court battle. The contest, it seemed, was between native prestige and British supremacy.